Introduction

Photogrammetry, the use of overlapping 2D photos to construct 3D models, touches us in ways we mostly never think about. Farmers use it in models to grow more crops, game developers use it to create lifelike characters, and urban planners use it for 3D city modeling, to name just a few examples. Yet one recent tragedy highlights the power of this form of reality capture in conveying one of our most precious assets: culture.

In response to this month’s fire that destroyed most of the collection in the National Museum of Brazil, Sketchfab, the platform for publishing 3D models, shared 25 photogrammetric models from the museum and asked for the public’s help to digitally reconstruct the museum’s collection.

Preserving cultural heritage is at the core of a museum’s mission, but that mission is at risk when visitations decline. According to one expert, cultural organizations globally are experiencing “negative substitution” where more people are leaving the market than entering it, creating a shrinking visitor base. This is “the driving reason for the decline in attendance to museums, zoos, aquariums, performing arts entities, and other visitor-serving organizations” (Dilenschneider, 2017).

Historic sites have been experiencing declining visitations for years. Attracting visitors to sites that are hard to get to is especially tough. Hearst Castle, the isolated former hilltop estate of newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst, knows this first hand. Tours taken at this National Historic Landmark numbered 775,958 in 2015, dropped 4.6% to 744,409 in 2016 and decreased another 15.5% to 628,858 in 2017, according to California State Parks (Tanner, 2018).

I hypothesize that using photogrammetry to create virtual models of remote, historically important landmarks would increase access for distant visitors and customers with a mobility disability while providing a visually rich and immersive storytelling experience.

Field Test

My original plan to test this hypothesis consisted of the following steps:

- Create a video tour of Hearst Castle using Google Earth Pro.

- Extract still images from the video using Adobe Premiere Elements.

- Create the 3D model from the still images with Autodesk ReMake.

- Prepare the final reconstruction on Sketchfab.

I would determine the success or failure of my hypothesis based on responses to a brief survey administered to those I asked to provide feedback.

Creating the Video Tour

Do you ever get the feeling from watching a video that you can easily tackle the task depicted, only to end up committing a bunch of false starts? That was the case here.

Inspired by Ben Kreimer’s seemingly idiot-proof video showing how he used photogrammetry to construct a 3D model of a large convention center, I set out to follow his technique.

My first step was to take a video of Hearst Castle using Google Earth Pro. I found this software to be quirky. One of the more irksome quirks is that, if you choose the right settings, you should be able to make the red balloons that identify sites disappear, like this:

Sadly, I found this to be only a temporary state, and as soon as you click on the screen again, the balloon reappears. I tried to replicate the “no balloon” state, but ultimately could not. That’s why I had to settle for an image like this as a starting point for my video:

I initially tried to capture all four sides of the property doing the video tour from about 1,800 feet “eye altitude” at 45°, but I found it difficult to execute clean turns at ill-defined corners of such a vast property.

That’s when I decided to do an aerial tour, as if you were circling the property from a helicopter. The goal was to replicate the experience of flying over Hearst Castle to provide a good sense of the surrounding terrain and the scale of the estate.

The hardest part of this was making sure the video was smooth, with no jerky or abrupt motions. I didn’t want sudden jumps in the video that might yield blurry or missing still images for the 3D model.

To give myself plenty of options, I executed seven tours of roughly 60 – 90 seconds each, all at an altitude of about 2,100 feet. I finally landed on a video that I was happy with.

Extracting Still Images

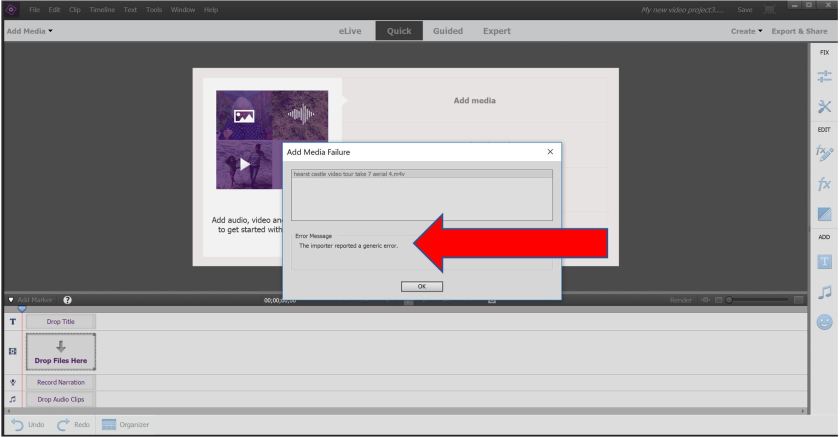

The next step was to pull still images from this video using Adobe Premiere Elements. I expected this to be a straightforward operation, but here too, I hit a speed bump. I was greeted with the message “The importer reported a generic error” as indicated by the red arrow below:

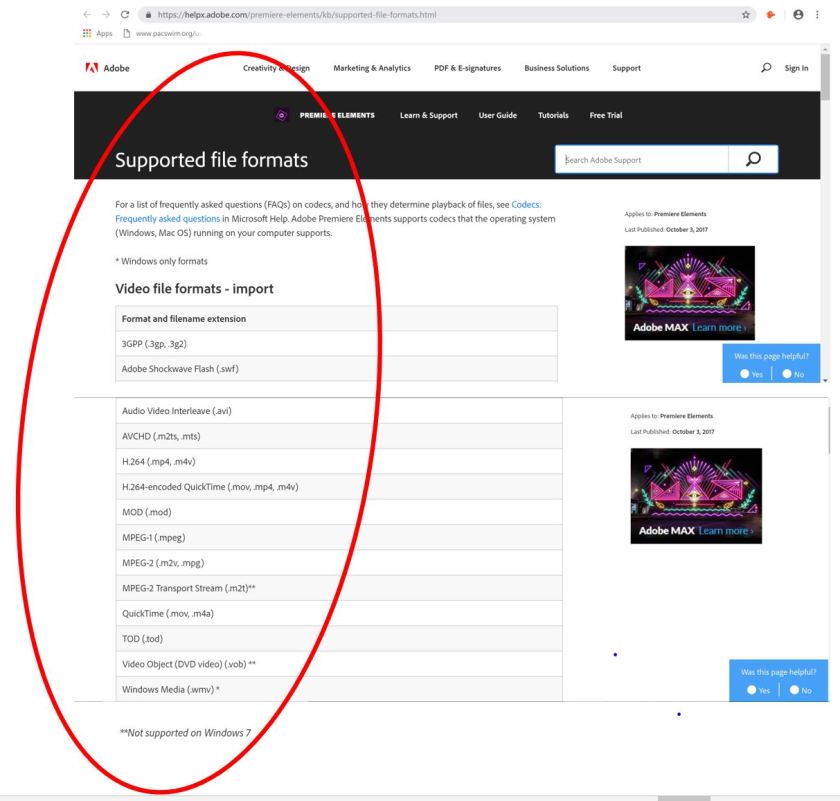

It turns out Premiere Elements does not support Google Earth Pro’s video format, M4V.

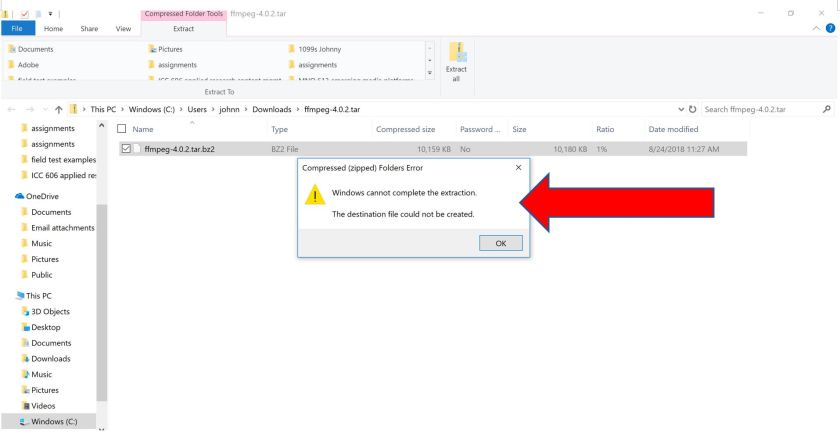

Per Kreimer’s recommendation in his video, I then tried FFMPEG, an open source multimedia framework, but my computer didn’t readily open it and I couldn’t find instances of people using it to extract still images from it.

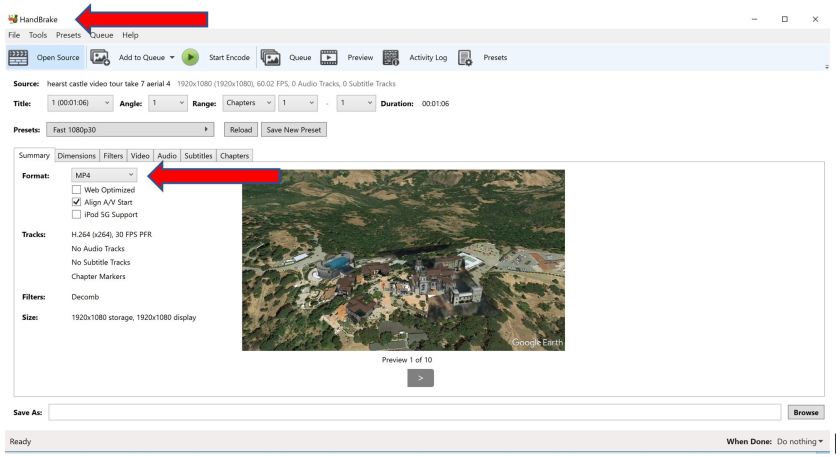

I next tried Handbrake, an open source video transcoding desktop app. I successfully converted the video from M4V to MP4.

(You can view the converted video at https://youtu.be/_ZYeNU6W-SE.)

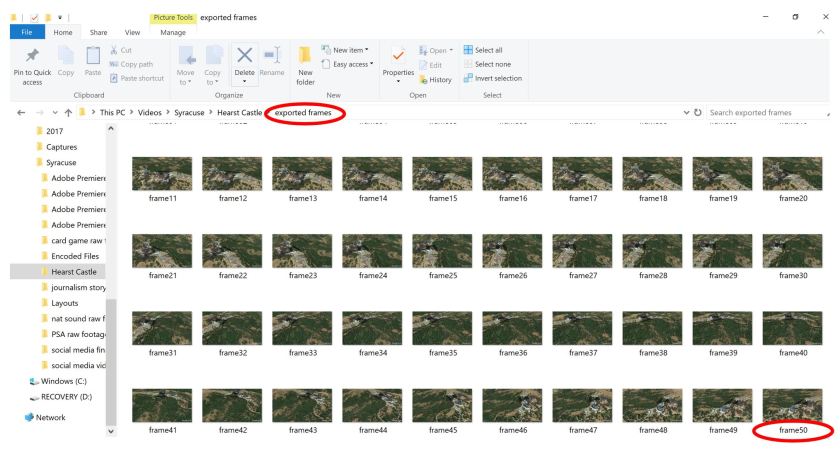

From there, I exported 50 frames using Premiere Elements. The 63-second video had 123 frames, so I exported roughly every other frame.

I exported this quantity because that’s the maximum number that the free version of photogrammetry software 3DF Zephyr allowed for my 3D reconstruction. (My original choice of software, Autodesk ReMake, had been replaced with a subscription product called ReCap Pro. ReCap Pro is free to students, but they get last priority for processing 3D models.)

Creating the 3D Model

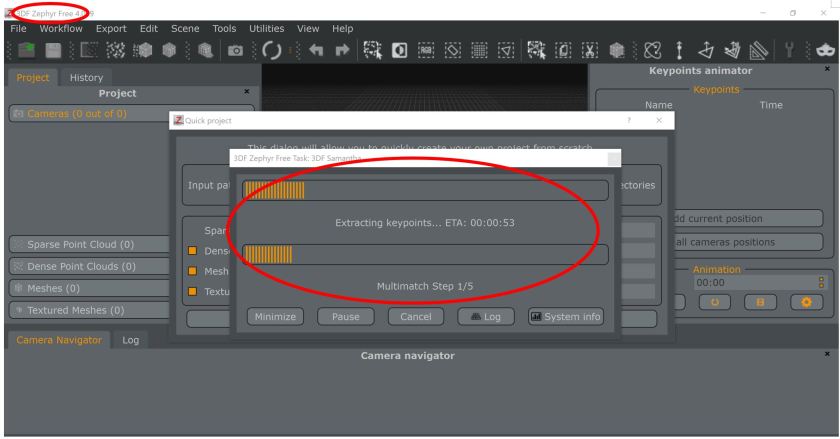

Now I was ready to build the 3D model. In 3DF Zephyr, I imported the 50 images that I had just extracted and waited as the model was constructed.

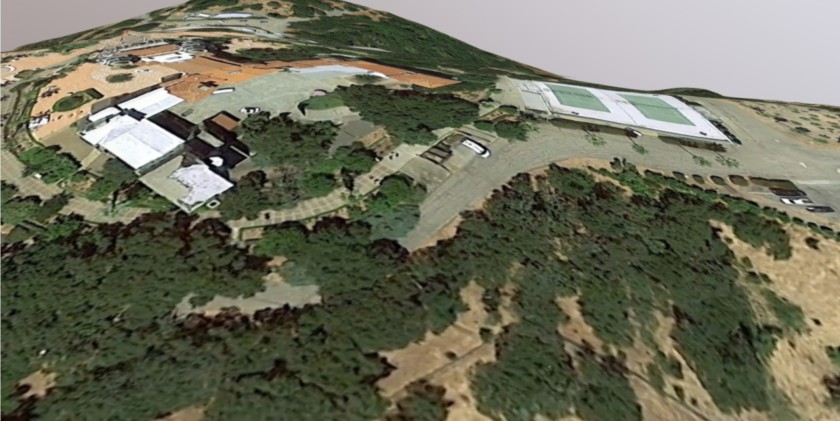

When it was all done, I was mostly happy with the outcome. One thing I didn’t expect was the model to look like a melting ice cream cake version of the real thing. That pesky red balloon was there, along with the label Hearst Castle emanating from it in multiple directions.

I tried again, this time using images from two other videos, but it yielded no improvement in either instance.

Just for fun, I tried one with the 3D Buildings layer deactivated on Google Earth Pro, but you couldn’t even make out Hearst Castle in the model:

Putting the Finishing Touches

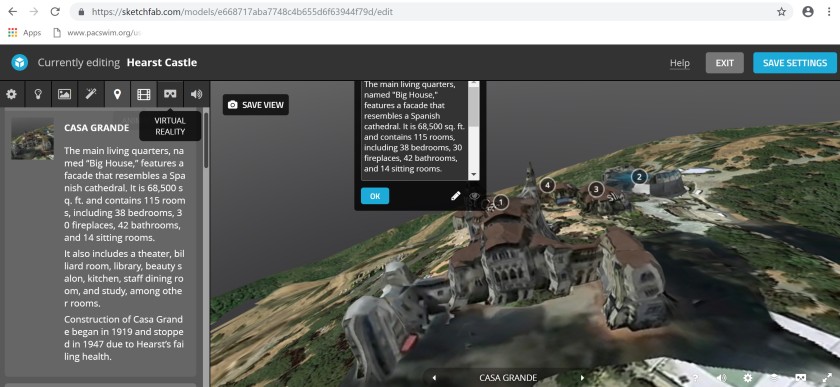

This step consisted of researching and preparing annotations, setting the point of view for each annotation, adding audio and settling on the final thumbnail and initial view of the model.

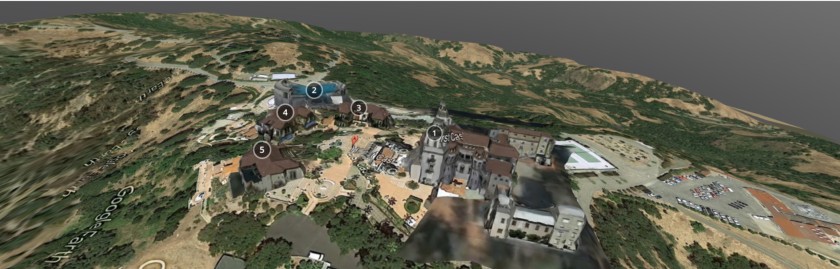

The free version of Sketchfab allows up to five annotations, which was perfect since there were five main structures within the estate that I wanted to highlight in the model (four buildings and a pool). I researched each one of them and distilled my findings into bullet points.

I then set the point of view for each annotation. This is Sketchfab’s way of presenting what the viewer sees when clicking each annotation. It essentially involves manipulating the model to give the viewer the perfect look at what they’re trying to see.

Here I ran into an issue: I wanted to give viewers a rather close-up look at each of the five highlighted structures. However, when it came time to set the point of view for each of the three guest cottages on the estate, I couldn’t adjust the perspective to the perfect spot hovering in the courtyard where the viewer could be right in front of each property. The level of control from my computer mouse just wasn’t that granular. I settled for a point of view that was higher and further away to give the viewer a bigger-picture perspective of the cottages relative to the entire estate.

To add storytelling and audio elements, I added a short audio clip of myself narrating a bit of copy about Hearst Castle and the five highlighted structures. This also served as a sort of guide to the viewer navigating the annotations.

I finished this part of the process by setting the final thumbnail and initial view to look like this:

You can experience the final 3D model on Sketchfab at https://sketchfab.com/models/e668717aba7748c4b655d6f63944f79d.

Surveying the Audience

This field test was intended to see whether virtual models of remotely located historical sites would fuel interest among distant or mobility impaired people in visiting them live. I envisioned my target audience to be people who were middle-aged or retired. While I would have liked to include younger people (e.g., Millennials) in my survey sample given their comfort with technology, I didn’t have ready access to this audience.

I emailed 12 people (10 men, 2 women) a link to the 3D model on Sketchfab along with a short survey. These people range in age from their early 50s to mid-80s. Before sending the email, I gave advance warning to look for it, including in junk mail. The email was as follows:

EMAIL:

Hi X,

I need your help answering a few questions for a school project.,

BACKGROUND

I’m taking a course in emerging media platforms at Syracuse where, for the final project, students conduct a field test using emerging technologies like virtual reality, 360-degree video, etc., to solve a media problem.

I’ve opted for photogrammetry for my field test. Simply put, photogrammetry is the use of 2D photos to make 3D models. Using Google Earth, I did a video aerial tour of Hearst Castle, then used still images from that video to create a 3D model of that landmark and the surrounding terrain.

MY HYPOTHESIS

I hypothesize that a virtual model of this remotely located National Historic Landmark would increase access for distant visitors and those with a mobility disability. Such a model would also provide a visually rich and immersive storytelling experience that currently does not exist today.

WHAT I NEED FROM YOU

Please click on the following link to view and interact with my 3D model of Hearst Castle, and then answer the questions that follow. (NOTE: I know that my 3D model is imperfect, but, fortunately, we are not being graded on how pretty our projects are, so no need to comment on that aspect.)

https://sketchfab.com/models/e668717aba7748c4b655d6f63944f79d

- If you’ve never visited Hearst Castle before, would an interactive 3D model like this increase your interest in learning about this landmark? If not, what would change your mind? What’s missing from the model?

- If you live far away or have a mobility impairment, would interactive 3D models of famous sites be something you’d seek out to be able to experience those landmarks from the comfort of your home? If not, why not?

- Do historical sites need to provide more access to distant and mobility challenged visitors through technologies like these? Why or why not?

- Does my hypothesis ring true? Why or why not?

Thank you!

Johnny

Of the 12 people I sent the email to, seven people responded. The five who didn’t respond never found the email (even though I confirmed email addresses and resent the email twice), forgot to respond, or had trouble accessing the model (due to older web browsers or discomfort with technology in general).

This is admittedly a very small survey sample and was rather unexpected given that I knew these people and thought they’d all respond. In retrospect, this was probably an unrealistic expectation. Any future test should include a larger sample to better validate the findings.

Key Findings

Key findings, along with quotes from some respondents, include the following:

- Interactive 3D models can fuel interest in visiting a historic site, guide planning for a trip, and deliver a supplemental experience to a live visit.

“I have visited Hearst Castle and you have to take a shuttle from visitor center to the Castle. They have 4 separate tours of the Castle. A 3D interactive model would help determine which tour would spark my interest.”

“A visual/virtual visit through 3D presentation would be a great way for people to check places out. A virtual visit from afar seems like it would be helpful to those who intend to visit. No question it would be a really great way to “show” those who are physically challenged with mobility. Those planning a visit would be well prepared to see ‘what they saw’ in person.”

One respondent, a college professor who teaches digital filmmaking, disagreed:

“An interactive 3D model was fascinating in the 90’s when the technology was new but today this would not increase my interest in the landmark. I’d rather watch a well produced video without the interactivity.”

- A model should convey a story and immerse viewers in a detailed virtual tour of the entire historical site.

Here’s where my model falls short, according to four respondents:

“The model does not provide much in detail when I bring it up close…just gets blurry. Since I do not get much visually, it does not hold my interest. The info on each building also is sketchy and does not draw me to it. There needs to be more story to this. If the model were set up so you could virtually walk around the grounds and in the buildings, that would be a draw.”

“As an interested viewer, I would probably be looking for more visuals, maybe more photos (exterior and interior), that would pop up when I clicked on the different structures or houses. This would give my mind some tools to put together a “sense of place”, a feeling of being there. In a more detailed version, I would want to see something similar to Google Earth “Street View”, but on a smaller scale, so as to give me the sense of walking from room to room inside or house to house outside, with 360-degree views.”

“Adding voice would be great and would be more captivating since more senses are now involved. Oh, the feelings and emotional aspects can really be highlighted with voice, sounds, music.”

“The 3D model will make my observation more interactive. It will give me the feeling I am there on the ground. Definitely the 3D will make my experience more satisfying. To answer what is missing, I would say I would like to see the inside of the building in 3D also. To go from the outside to the inside is a big step in grabbing my attention.”

- Most believe publicly owned and maintained historical sites should offer 3D models to better serve citizens.

“Government owned landmarks and historical sites do have some obligation to provide the general public with both real-life access and virtual access, taking advantage of the newest technologies, in order to educate, enlighten, and even entertain those interested in seeking out that information and experience.”

“If you can’t visit site like Eiffel tower, the Vatican in Rome or Castle in Germany, a 3D interactive model can help learn about the history without the cost of travel or waiting in long lines.”

“Yes, historical sites need to use 3D technology to capture distant and mobility challenged visitors. As this technology matures, I believe this will become a standard and will become the bar expected from internet sites.”

Again, the college professor disagreed:

“A video can quickly and easily convey the same information without the interactivity. The interactive 3D model may only run on one site and could have inherent compatibility issues with different browsers, operating systems, and mobile devices. Video is a proven medium and works on all platforms.”

Conclusion

This field test demonstrates that photogrammetry can play a role in expanding public interest in experiencing remote, historically significant landmarks. It has particular appeal for customers who value the additional information and perspective that a 3D model can offer to support trip planning. If delivered as part of an integrated multimedia and storytelling experience, a clear and detailed virtual model can whet the appetite of a customer who is considering a visit to a historic site and perhaps drive advance ticket sales.

Those who live far from a site, can’t get around easily or prefer not to travel would also benefit if they prefer the convenience of experiencing a site from the comfort of home. There may even be some who are willing to pay for such a virtual experience. Potential business models tied to this intended use was beyond the scope of this test, but it’s worthy of more study.

One way to improve this technology to have maximum impact is to make it simpler. Models for historic site visitations shouldn’t be over-engineered. While they must offer something you can’t get from land-based tours or a well-produced video, the interactivity and navigation shouldn’t overwhelm the customer by providing too many options or by making it onerous to figure out or access.

A way to mitigate the complexity is to offer two options, one with interactivity and one without it. The first could be a virtual experience where the viewer passively watches a guided 3D tour enhanced with narration and doesn’t interact with the model at all. This might be well received by those who are technologically challenged. The second option could give viewers a multimedia experience with the ability to interact with 3D, photos, videos and audio.

Of course, all of this is moot if 3D models can’t be accessed with ease. Several of my potential survey respondents had trouble accessing my model (including on their mobile phones) and thus couldn’t complete the survey. During this test, Google updated its Chrome browser, which resulted in compatibility issues with Sketchfab. Photogrammetry needs to overcome these growing pains.

Another challenge is that the technology is not well known to the masses. As ubiquitous as photogrammetry is, it is still largely practiced behind the scenes by highly specialized professionals for industrial applications.

The options for consumers to experience it first-hand in cultural applications are growing. For example, CyArk, a nonprofit dedicated to documenting and sharing the world’s cultural heritage, released an app last February for Oculus Rift and Gear VR that enable viewers to take 3D tours of four heritage sites spanning three continents and 3,000 years of history. Two months later, CyArk partnered with Google to launch Open Heritage, an initiative that offers 3D tours of 27 cultural sites around the world. PBS’s “Ancient Invisible Cities” uses 3D scanning to give unprecedented looks at Cairo and other cities of the ancient world. The Smithsonian Institution’s 3D lab uses photogrammetry and other methods to digitize objects that are viewable online.

These are big-budget, resource-intensive operations that likely put photogrammetry out of reach in the near term for most historic sites. Until costs come down, 3D models become easier and faster to generate, and compatibility kinks get ironed out, virtual historic site visitations on a mass, global scale will have to wait. In the meantime, larger venues spanning the culture and entertainment spectrum will innovate with new use cases for virtual visits using photogrammetry, cloud solutions for reality capture will become more powerful, and next-generation mobile apps will emerge to put incredibly lifelike 3D modeling capabilities in the hands of billions of consumers, creating the perfect storm for virtual historic site visits to take off.

Sources

Captain, S. (2018, April 16). Google’s new VR tours let you experience imperiled cultural sites around the world. Fast Company. Retrieved from https://www.fastcompany.com/40559363/googles-new-vr-tours-let-you-experience-imperiled-cultural-sites-around-the-world

Dilenschneider, C. (2017, January 25). Negative substitution: Why cultural organizations must better engage new audiences fast (Data). ColleenDilen.com. Retrieved from https://www.colleendilen.com/2017/01/25/negative-substitution-why-cultural-organizations-must-better-engage-new-audiences-fast-data/

Hayden, S. (2018, February 17). VRtour app ‘MasterWorks’ uses photogrammetry to bring you to 4 fully explorable heritage sites. Road to VR. Retrieved from https://www.roadtovr.com/masterworks-uses-photogrammetry-take-guided-vr-tour-4-fully-explorable-heritage-sites/

Historic site visits. (2016, February). HumanitiesIndicators.org. Retrieved from https://www.humanitiesindicators.org/content/indicatordoc.aspx?i=101

Kreimer, B. (2016, July 27). Export Google Earth 3D models for VR. BuzzFeed. Retrieved from https://www.buzzfeed.com/benkreimer/google-earth-3d-for-vr?utm_term=.gok5XWn7P#.hqRQe4laV

Tanner, K. (2018, January 31). Hearst Castle attendance slides as highway closures take a toll on local businesses. The Tribune. Retrieved from https://www.sanluisobispo.com/news/local/community/cambrian/article197607334.html

Wilkening Consulting. (2018). Museum visitation rates: A myth-busting data story. WilkeningConsulting.com. Retrieved from http://www.wilkeningconsulting.com/uploads/8/6/3/2/86329422/wilkening_consulting_museum_visitation_data_story.pdf